Experiential chronicling: STIR reflects on impactful visits that widened perspectives

by Jincy IypeDec 31, 2024

•make your fridays matter with a well-read weekend

by Anmol AhujaPublished on : May 17, 2024

Unravelling through the rather sequential layout of RIBA’s Architecture Gallery, the didactically named exhibition—the act of 'raising the roof' presumably implying challenging the status quo in British architectural practice—opens with a contradiction, a slight provocation that sets the stage for the rest of the exhibition. “We are asked today to think imperially, to strengthen and consolidate the bonds that bind this empire together. Those bonds are political, industrial, and economic,” reads a quote by Harry Barnes from 1934, then Chairman of the body’s Registration Committee. Juxtaposed against it is current RIBA president Muyiwa Oki’s statement: “We can’t change the past, but we do have a responsibility to understand and learn from it,” echoing the historic institution’s hopefully current ethos, of which Oki—the RIBA’s first president-elect of colour, also its youngest, and an architectural worker—is very much a personification. Raise the Roof: Building for Change is awash in that currency and optimism. While seemingly approaching the future of the institution and the profession at large with diversity and hope, its view of colonial history can appear somewhat static, a distant reference point from which to steer away. Admittedly strides ahead, the condition of post-coloniality begets an understanding of colonialism and imperialism (cc: gender, ethnicity and race, never mutually exclusive) as a kind of ‘slow violence’ that manifests in myriad ways in the present and evolves with every fraught political misalignment. In that, the showcase’s spiritual self is unbound, but its physicality within the austere RIBA building itself, though a herald for change, ties it down with the other ‘artefacts’ concurrently housed there—ones that it actively disengages with, disavows, and allegorically dismantles. The weight of empire then is a weight it cannot (and perhaps should not) shake off, making sure that every such victory is solemn and bittersweet, especially for peoples of the diaspora who are now welcomed into the building and the larger ethos of contemporary British architecture and city-making. It is a parable of hope for the hopeful; for the cynic, there is an unmistakable context to continually draw from.

Building on a brief to “interrogate and respond” to specific interior features at the renowned RIBA headquarters in London, four new commissions by the RIBA to artists of colour arguably look to ‘bring them down’ (in figurative terms, of course), addressing their overtly racist tones, and the reminders they serve of a woeful colonial history. Under the curatorship of Margaret Cubbage, artists Thandi Loewenson, Giles Tettey Nartey, Arinjoy Sen and Esi Eshun adorn the RIBA’s Architecture Gallery with reimaginings—or responses—to these outmoded interior features. The ones specifically in question are the Jarvis Mural, adorning the back of the Henry Jarvis Memorial Hall of the RIBA’s headquarters, and the Dominion Screen, an ordered bricolage of carved timber panels affronting the Henry Florence Memorial Hall on the upper floor. While materially and technically different, the two essentially planar adornments are replete with symbols and imagery that celebrate the might of the British empire—and by extension the plight of its colonies—at the time of the building’s construction and opening in 1934.

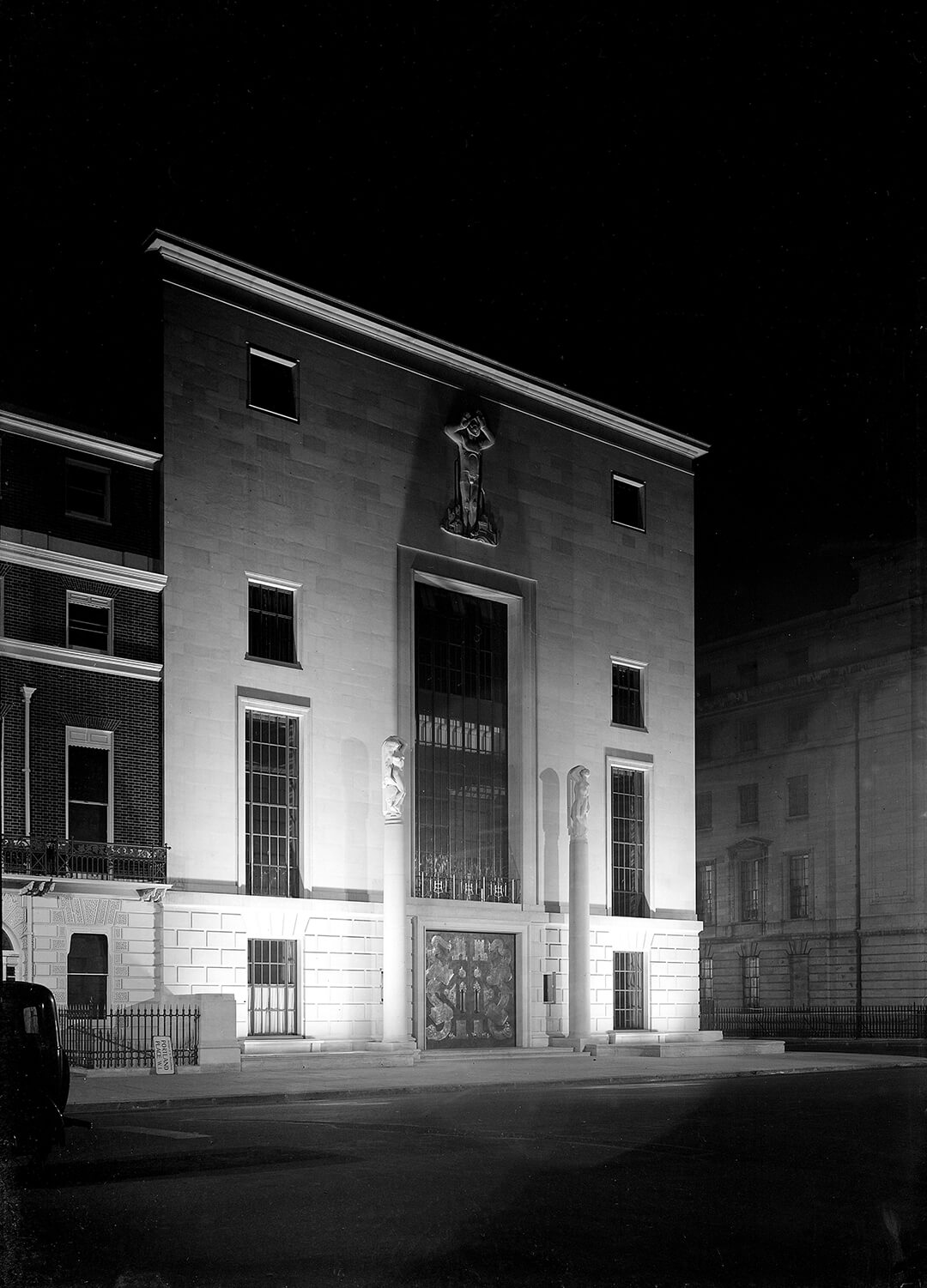

The distinctive premises, designed by George Grey Wornum using a mix of modernist and art-deco sensibilities, served to be the seat of the council of British architects that expanded the empire’s influence through sizeable built projects in colonies, reaffirming the agency of architecture in the imperial project. Designed to exert power, influence and wealth in nations otherwise drained by plunder and an exodus of natural resources to the British mainland, the architectures in these colonies, especially apart from strictly administrative structures, seemed to develop along hybrid directions. The Indo-Saracenic style comes to mind, apart from the ‘tropical’ twist on modernism that transformed North African nations and an erstwhile undivided Indian subcontinent into laboratories of an adaptive version of Western Modernism more suited to local conditions. Helmed by British architects albeit only in the first quarter of the 20th century, this was an aspect touched upon but still largely omitted from the V&A’s recent examination of the phenomenon in its ongoing exhibition, Tropical Modernism, ultimately an underwhelming showcase. The RIBA’s staging of its own exhibition that addresses the locus of this architectural proliferation is charged by that backdrop and its current stewardship under Muyiwa Oki, as well as Prof. Lesley Lokko being awarded the RIBA Gold Medal in a ceremony held in the same week as the exhibition opened.

Raise the Roof: Building for Change at the RIBA, at the heels of several such progressive developments, is thus touted to be only a primer in what is supposed to be a series of regimental changes that not only address but also perhaps overturn the institution’s complex history of complicity through both systemic and quite tangible, physical means, several of which are still at view at Portland Place. The Jarvis Mural especially, for instance, depicts the RIBA Council at its centre, surrounded by buildings that were seats of imperial power in colonies—administrative and otherwise—designed by British architects including Edwin Lutyens, Herbert Baker and the lot. The fringes of the composition are occupied by indigenous peoples from India, South Africa, Canada, and Australia, drawn up in increasingly offensive stereotypes of colour and sartorial choices, indulging in perceivably uncouth activities including perching/ squatting, dancing, and breastfeeding. The dual implication of the British architect being at the centre of the cultural liberation of colonies inflicted by ‘backward’ cultures is not with a hint of latency in the mural, now in a state of extreme disrepair and physical wear and tear.

In fact, its in-depth visual examination is made possible solely by digital means, since up close and in person, the screen seems to be covered by dust and grime, a fitting allegory to the ways of the empire. The slightly less offensive Dominion Screen, the second outdated artefact from the RIBA building that invited distant intervention and reimagining for this exhibition, uses the prized ‘empire timber’ from Canada to depict the resource abundance, people, and flora and fauna of the Commonwealth. “It was intended to be celebratory, but with modern awareness of colonial legacies its exploitation of natural resources and primitivist depictions feel problematic,” states the official RIBA website, based on extensive research conducted by Dr. Neal Sashore, Head of the London School of Architecture. Interestingly, Sashore will also be involved in the overall physical and systemic refurbishment of the RIBA building through the ‘House of Architecture’ programme, of which the exhibition is just the first step. “I welcome this opportunity to critically engage with the building’s—and by extension architecture’s—complex past and imagine a hopeful and more inclusive future,” states Sashore in an official release, terming measures like the exhibition “long overdue” for the RIBA.

The artists’ responses to the offence of these visual surfaces assume nearly the same dimensions and subversive proportions. Thandi Loewenson’s Blacklight is startling and stark, using swathes of her signature graphite strokes in layers, in cascades, with unmistakable connotations of colour and race, to draw attention to the exploitative and extractive nature of the empire, especially owing to its extensive mining activities in the African subcontinent. Assisted by Zhongshan Zou, Loewenson’s work is accompanied by a haunting, personal essay and uses the glimmer of the work’s metallic base to point to the fallacy of working with the earth. “I was just struck by how dirty it was,” she stated during a preview of the exhibition on-site at the RIBA, alluding to the poor ageing of the Jarvis Mural. She laments the erasure of mines and mineral extraction sites— ironically the home of some of the precious stones used to clad the building’s pomp—from the mural, occupying the fringes of her artwork with testimonies of mine workers told akin to tales. Giles Tettey Nartey’s horizontalisation and distortion of the Dominion Screen is devoid of iconography, instead operating as a table that invites collaboration and dialogue from all stakeholders across different strata in the profession—especially nations and people who were relegated to the fringes in the original compositions, seemingly intent only with gazing upon their colonial saviours. Designed in all black, Nartey’s subversion is handsomely tactile, inviting physical participation and interaction, and notably the only work of the four that is partly functional and expansive along three dimensions.

Moving away from the monotones, Arinjoy Sen’s digital illustration, The Carnival of Portland Place, is an explosion of colour that is itself in resistance to the muted sensibilities of colonial modernism, and in line with the oft misperceived conceptions of colour as linked to the colonial gaze over indigenous cultures, casting them as primitive and less evolved. As the name suggests, the piece charts a celebration, a coming together of cultures, races, and ethnicities to stage a carnival-like celebration right outside the RIBA building. It is riotous, playful, and queer—terms that are far from the RIBA’s steeped in traditional optics. Multidisciplinary artist Esi Eshun’s response develops along an archival front, using an audio-visual display to integrate and examine the narratives behind some of the buildings featured in the Jarvis Mural. Perhaps the most directly responsive to the dynamic nature of the colonial project as mentioned before, Eshun’s work harps on “the concept of time and how the iconography is a depiction of the notion of Empire as an edifice within a moment in history, and that history has over time been constructed and deconstructed but with an element of permanence especially within the fabric of 66 Portland Place." Elsewhere, the hall is adorned with and features two-dimensional patches and straps of geometric motifs, along with burlap strung through the exhibition space. Its subversions on the surface and off, Raise the Roof toes the line between institutional responsibility and the pitfalls associated with institutional correctionalism and tokenism. As a foray into larger conversations, it’s an extremely enticing work-in-progress.

Raise the Roof: Building for Change is currently running at the RIBA Architecture Gallery at 66 Portland Place, London, and will continue until September 21, 2024.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of STIR or its Editors.)

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 25, 2025

Middle East Archive’s photobook Not Here Not There by Charbel AlKhoury features uncanny but surreal visuals of Lebanon amidst instability and political unrest between 2019 and 2021.

by Aarthi Mohan Sep 24, 2025

An exhibition by Ab Rogers at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, retraced five decades of the celebrated architect’s design tenets that treated buildings as campaigns for change.

by Bansari Paghdar Sep 23, 2025

The hauntingly beautiful Bunker B-S 10 features austere utilitarian interventions that complement its militarily redundant concrete shell.

by Mrinmayee Bhoot Sep 22, 2025

Designed by Serbia and Switzerland-based studio TEN, the residential project prioritises openness of process to allow the building to transform with its residents.

surprise me!

surprise me!

make your fridays matter

SUBSCRIBEEnter your details to sign in

Don’t have an account?

Sign upOr you can sign in with

a single account for all

STIR platforms

All your bookmarks will be available across all your devices.

Stay STIRred

Already have an account?

Sign inOr you can sign up with

Tap on things that interests you.

Select the Conversation Category you would like to watch

Please enter your details and click submit.

Enter the 6-digit code sent at

Verification link sent to check your inbox or spam folder to complete sign up process

by Anmol Ahuja | Published on : May 17, 2024

What do you think?